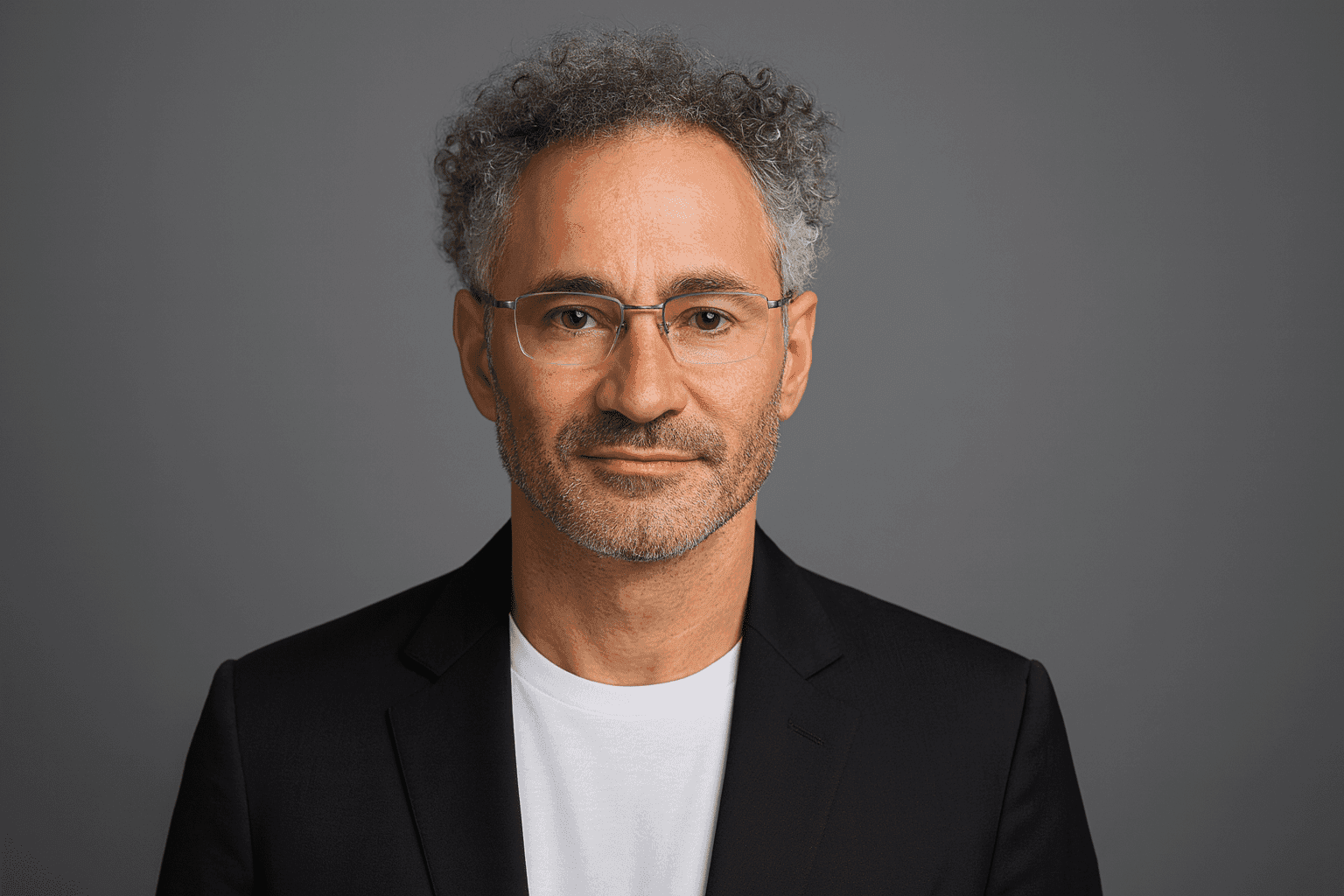

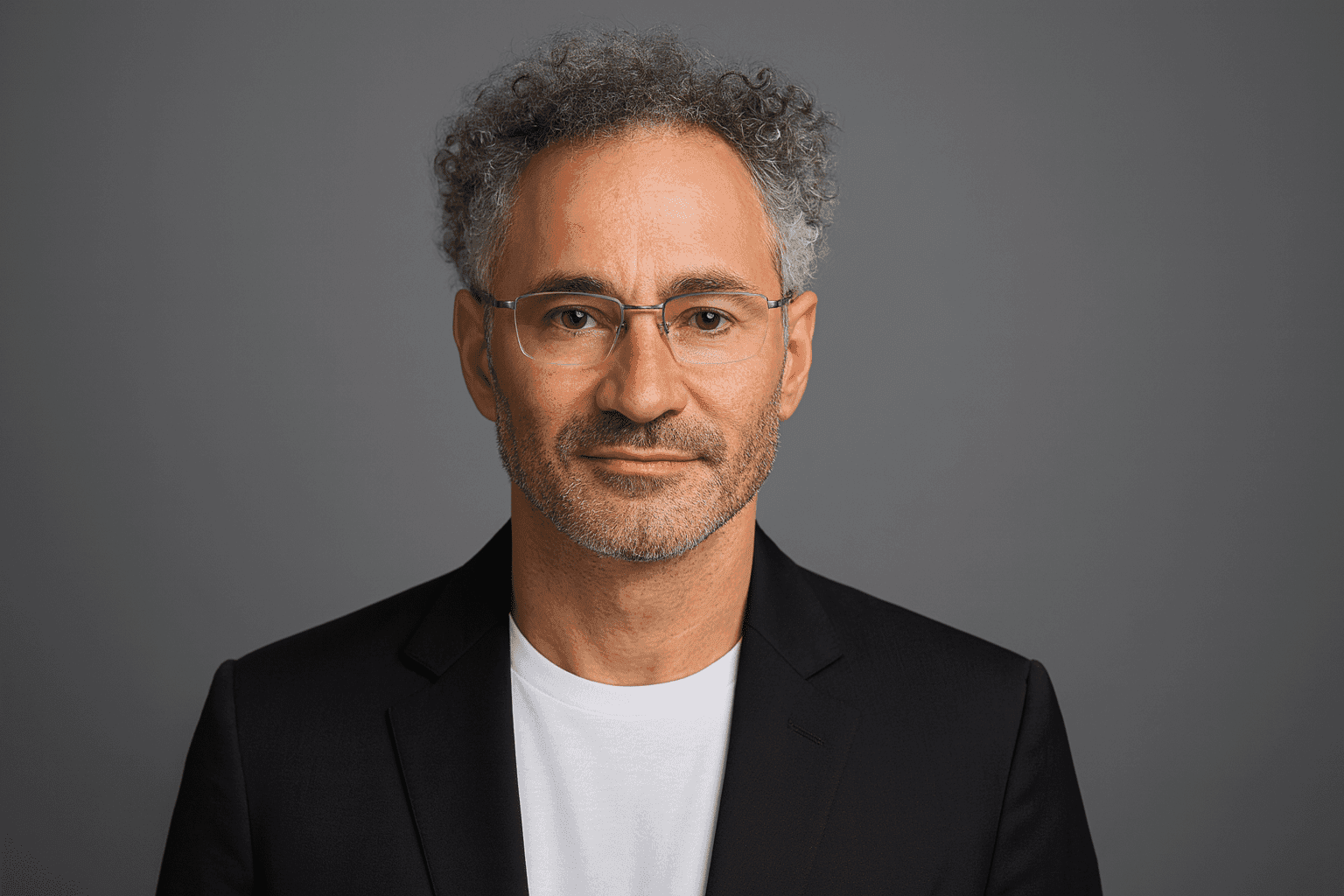

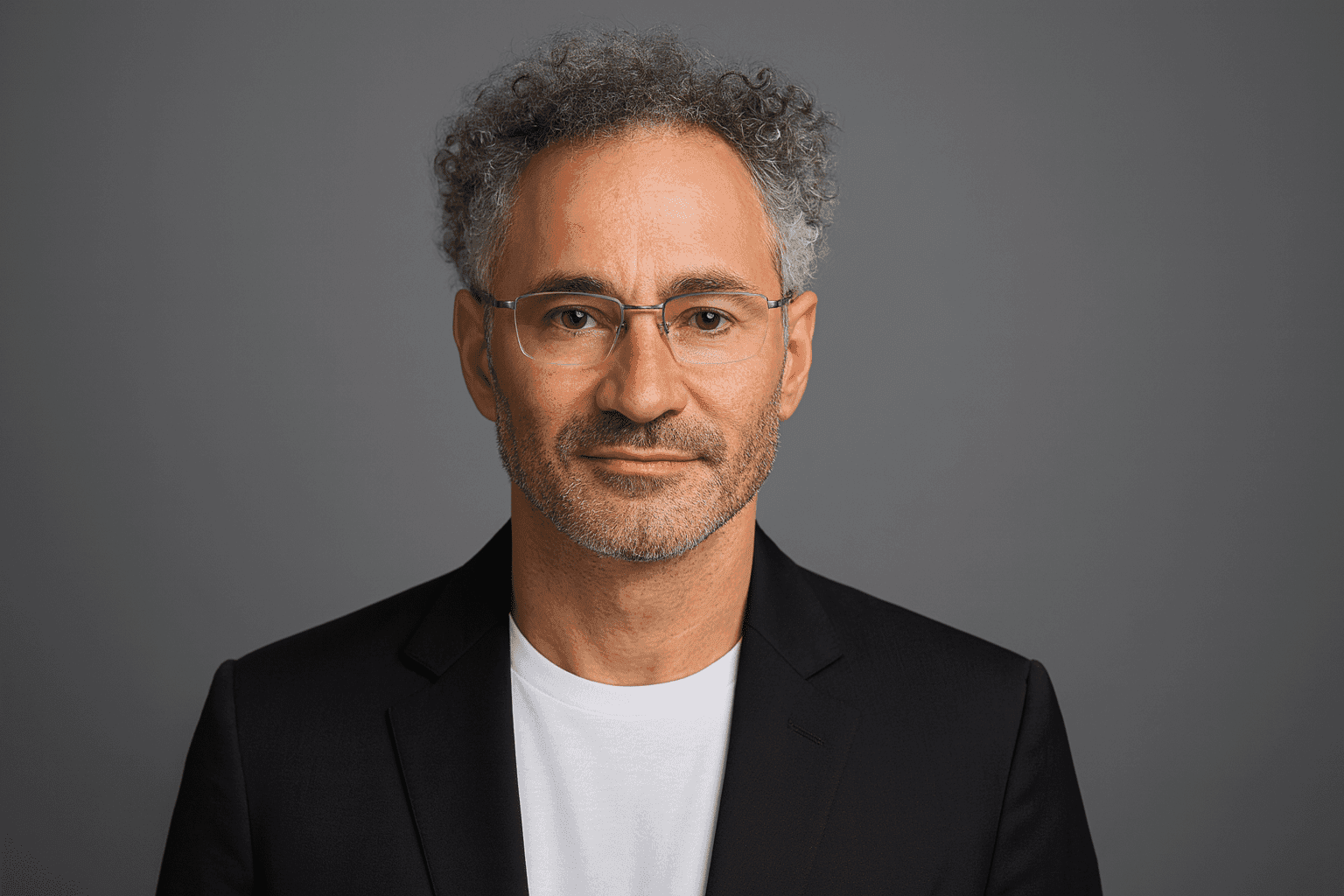

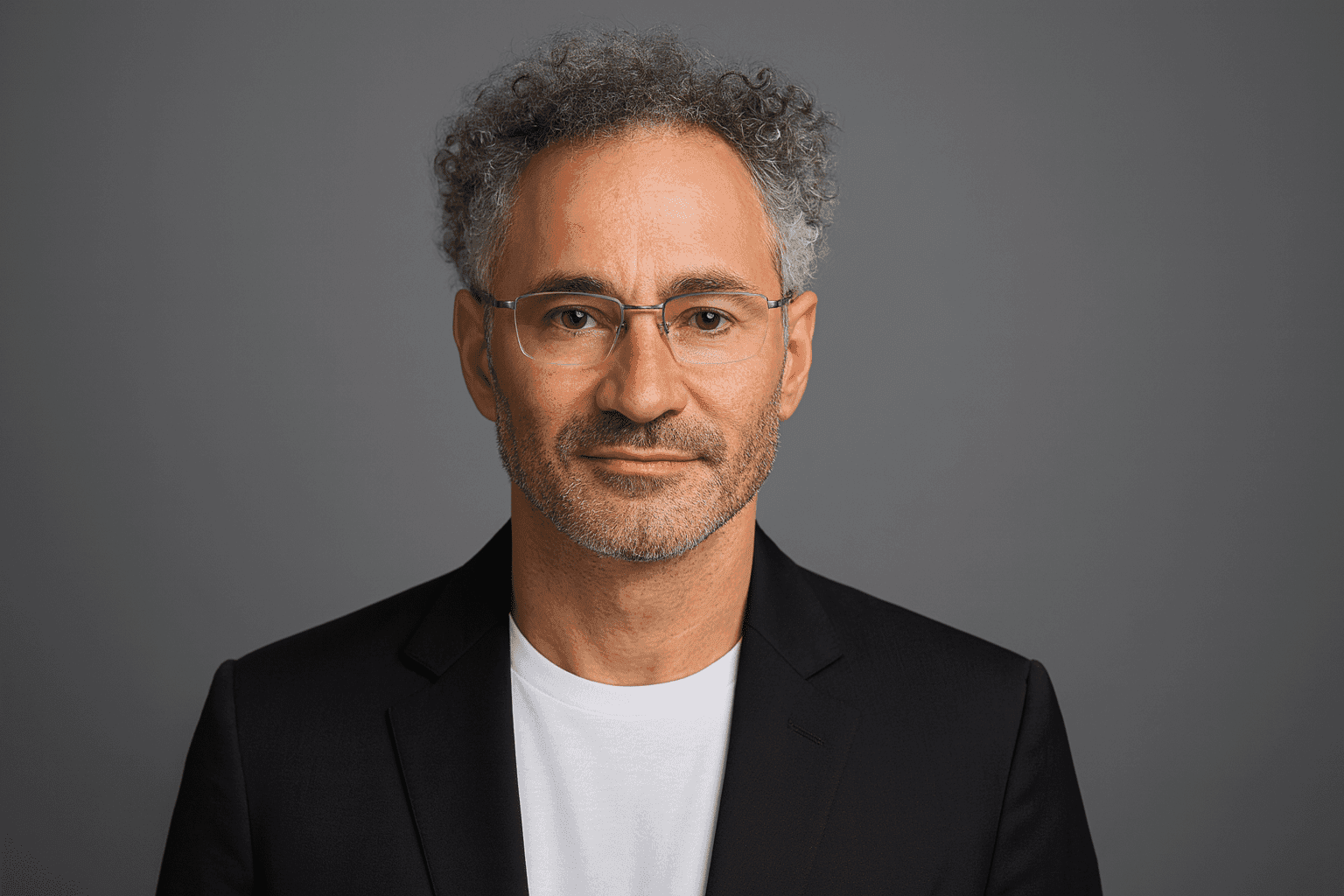

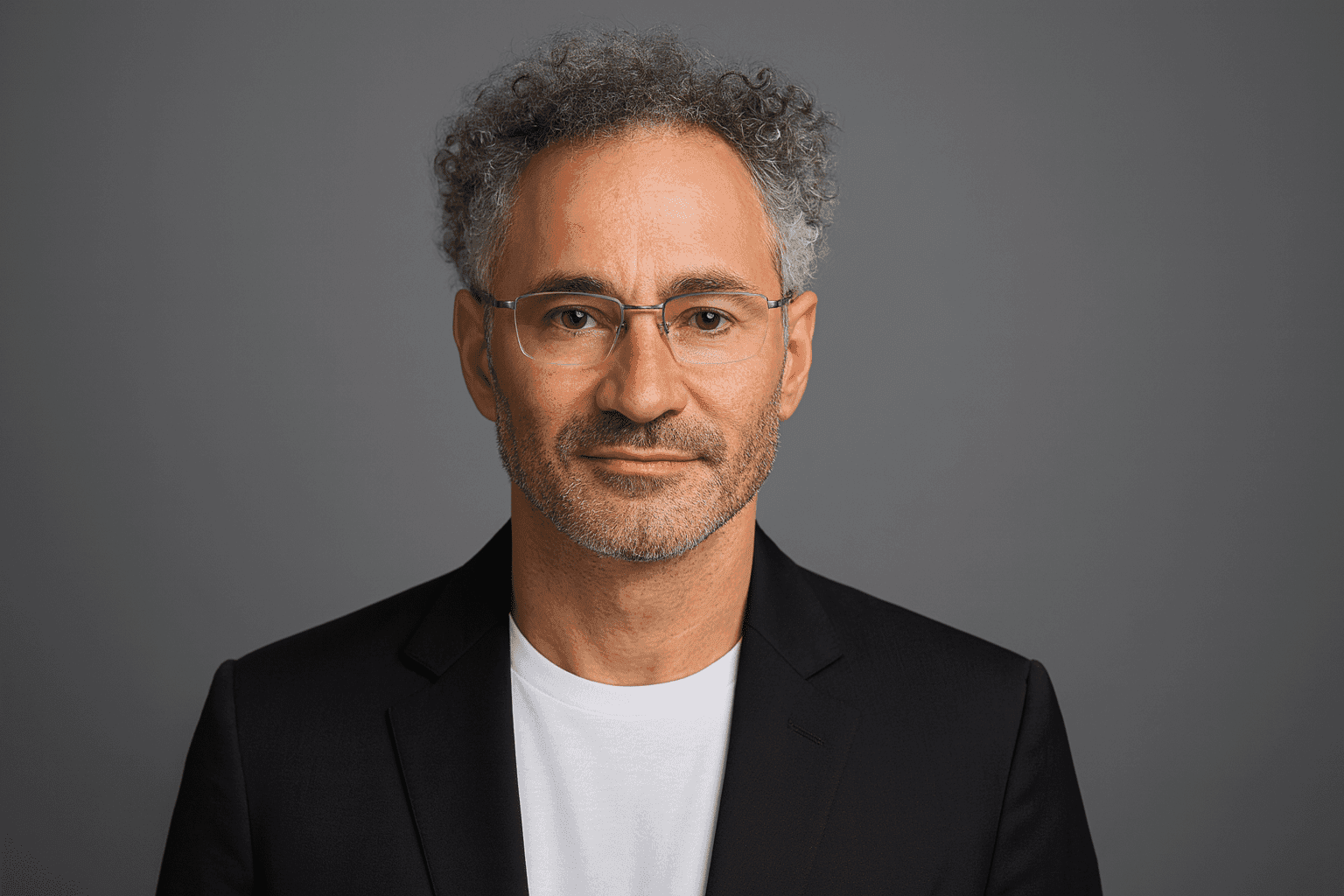

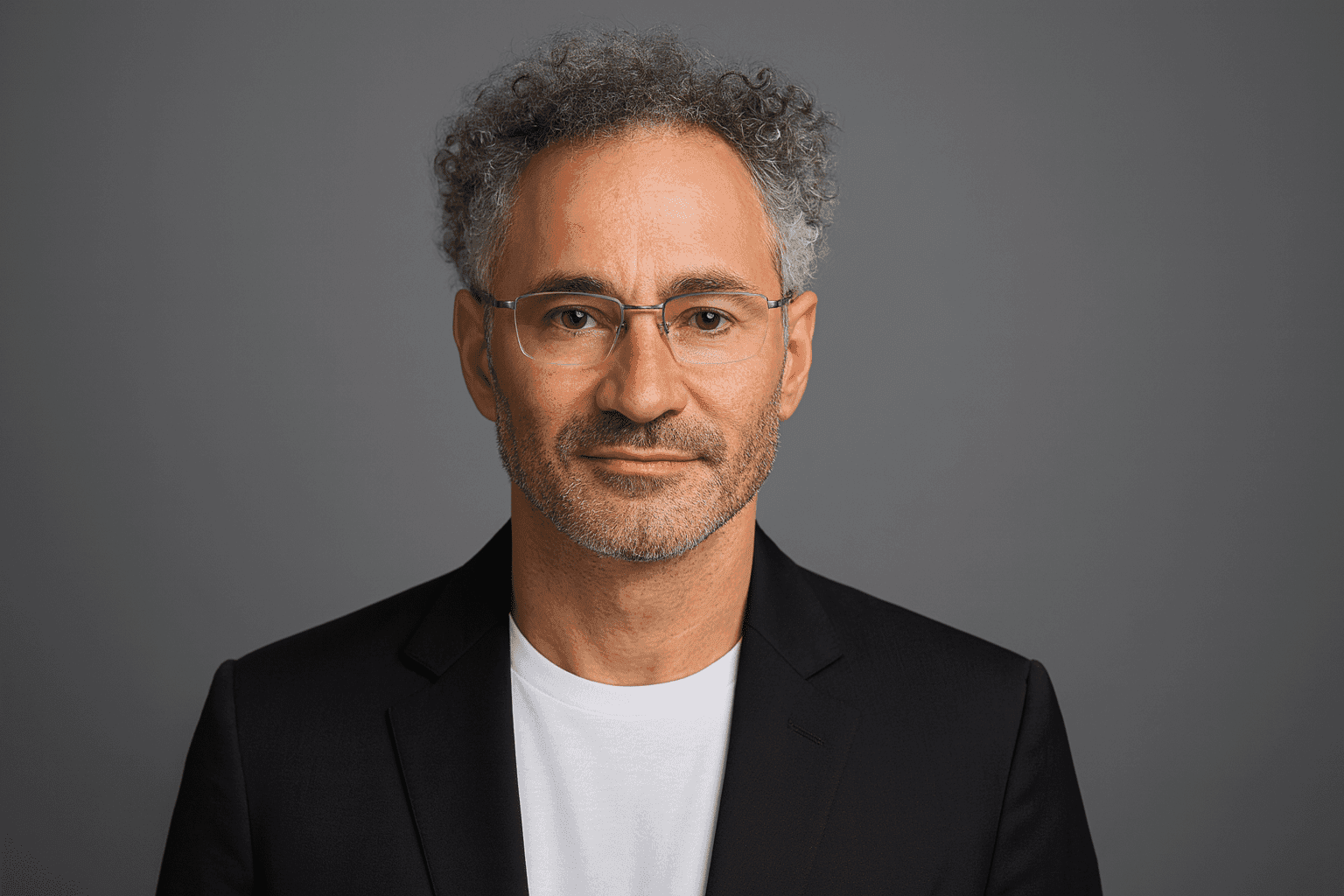

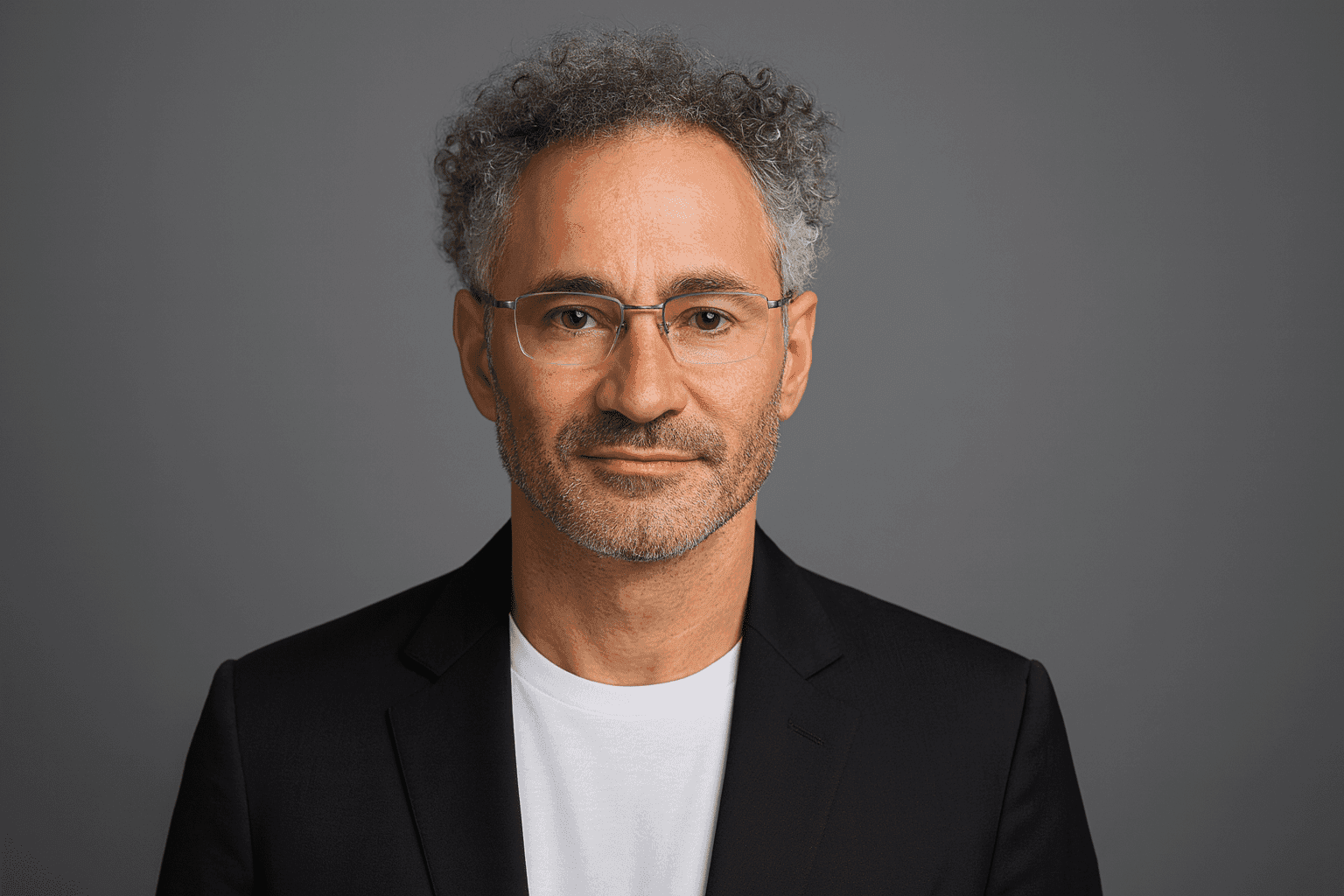

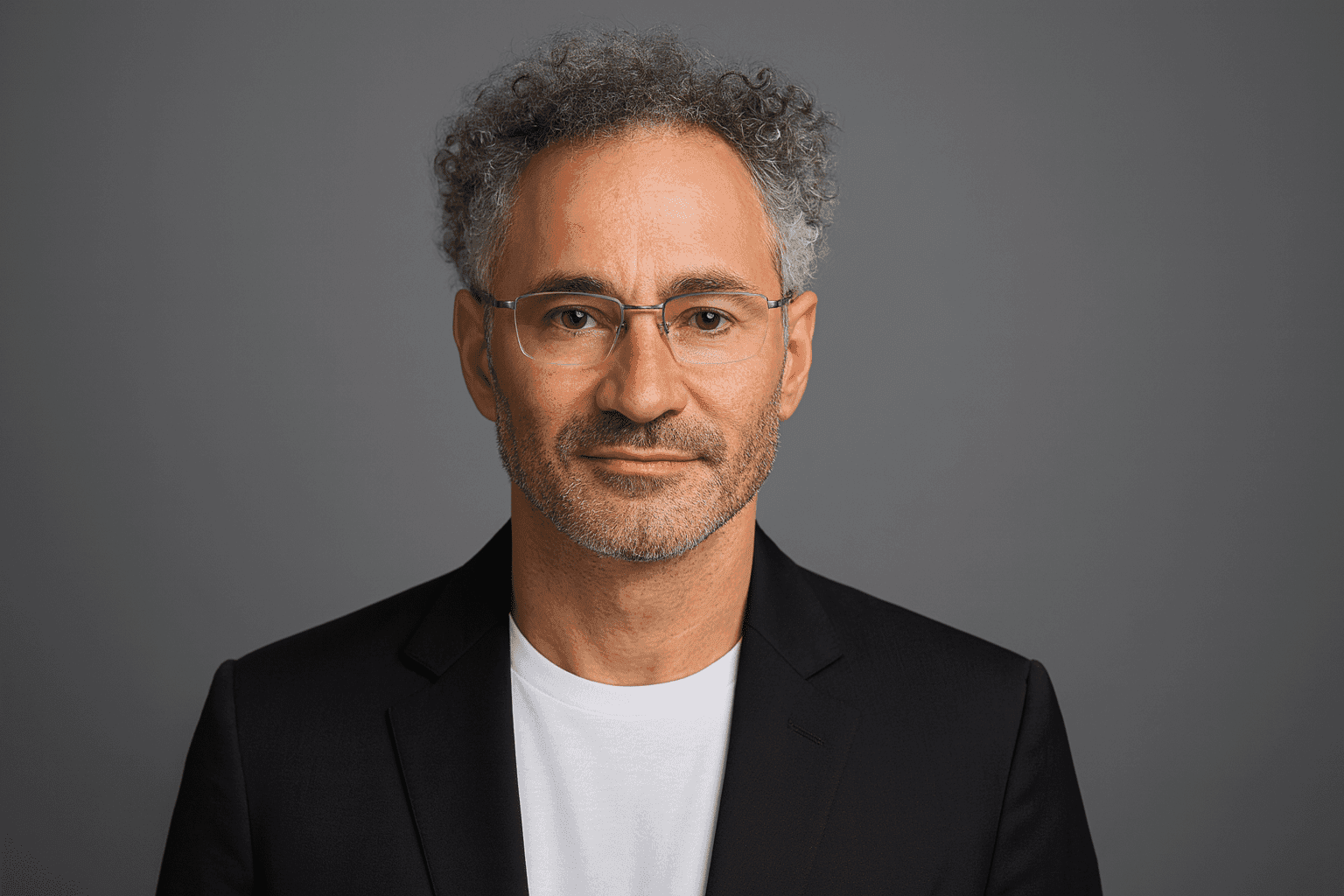

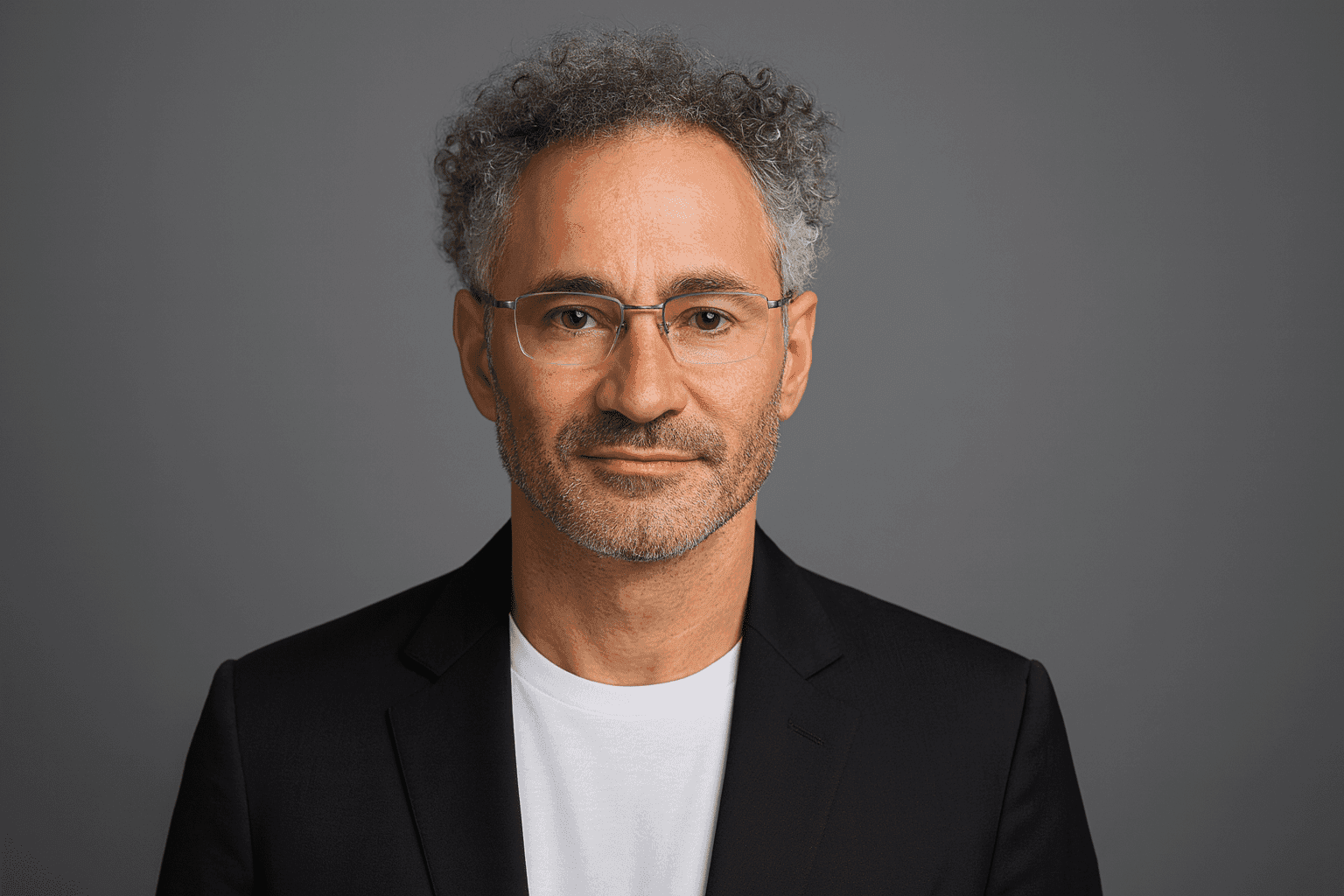

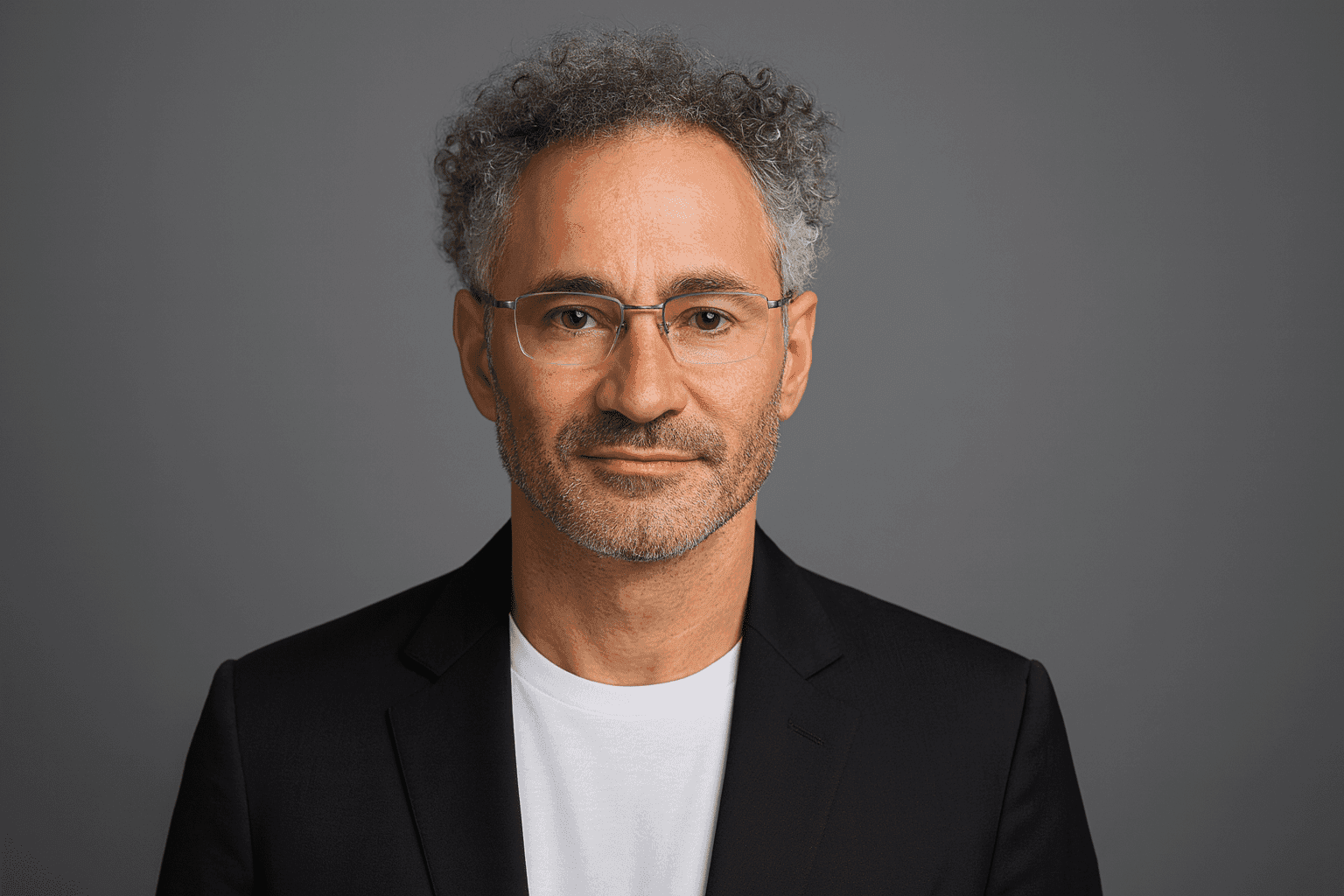

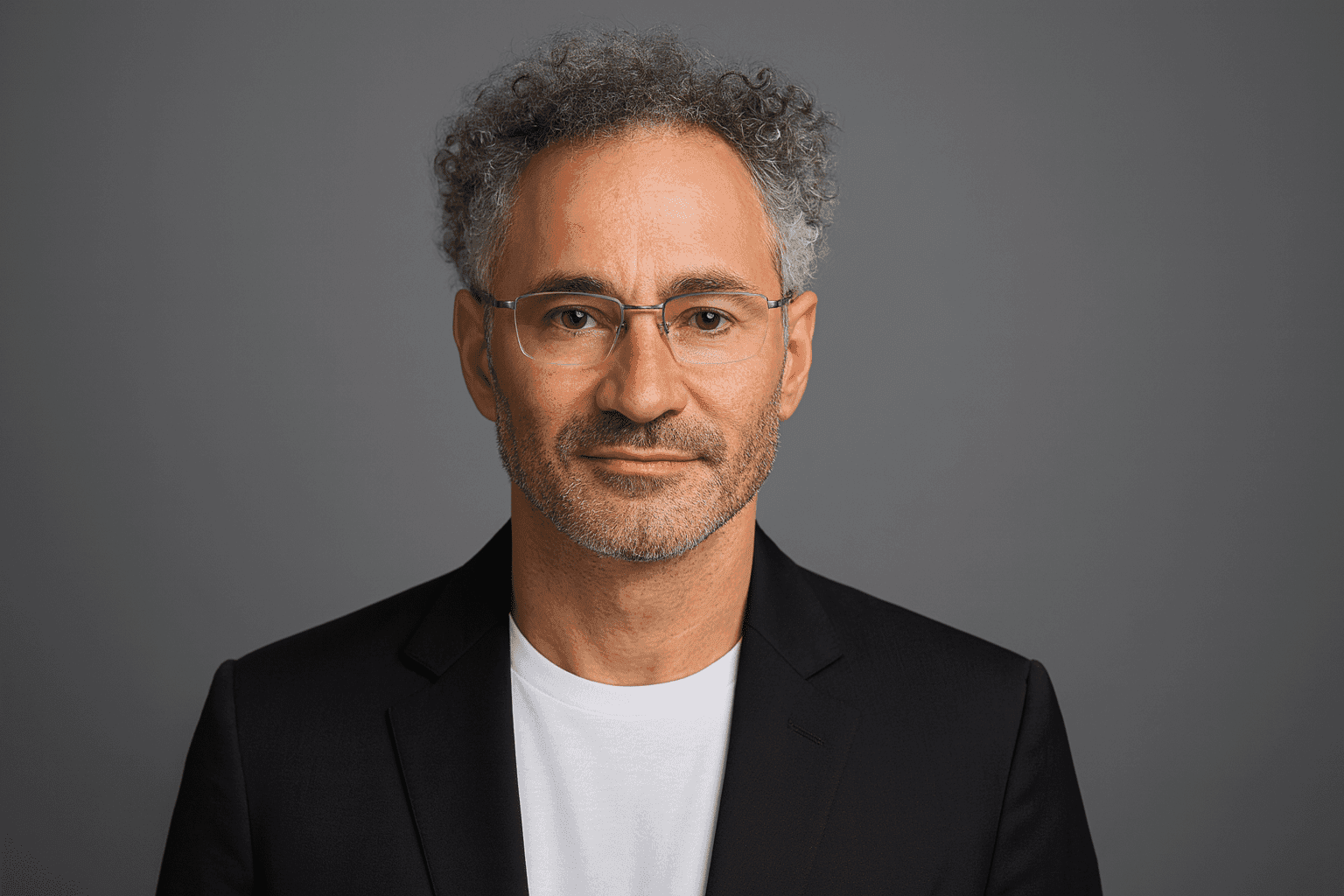

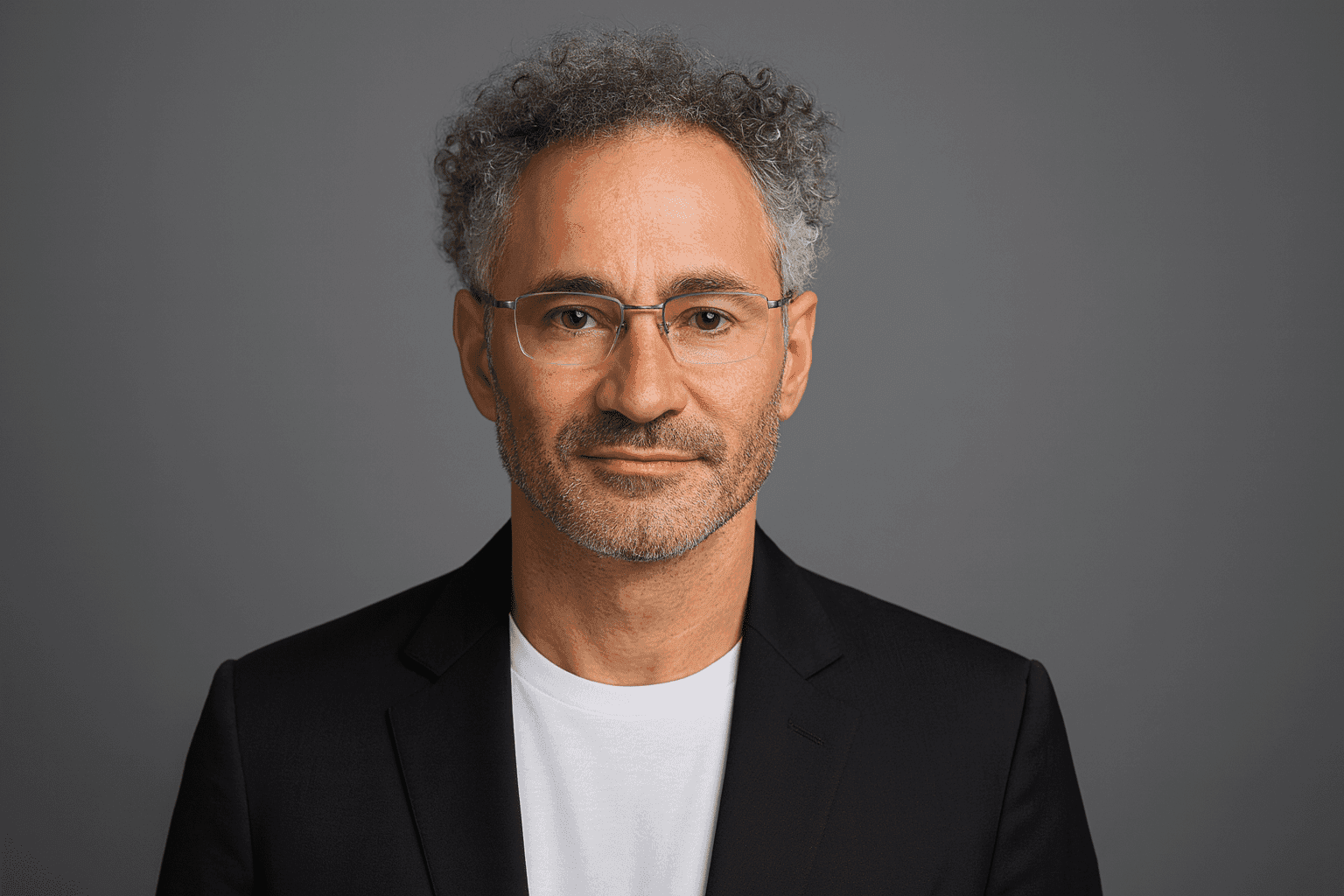

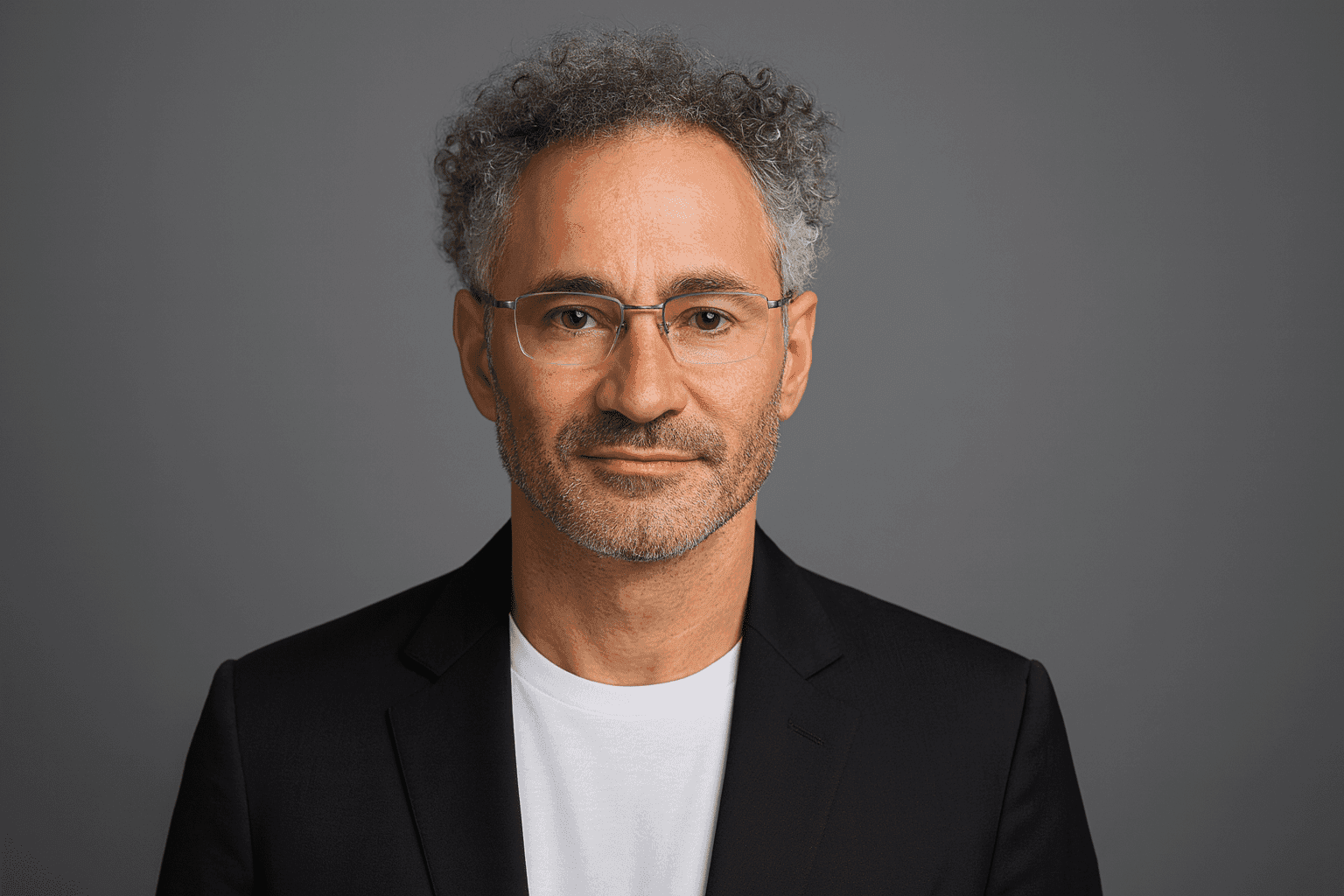

Alex KarpCo-founder & CEO

Alex Karp has spent two decades building Palantir as a “freak show” that breaks every playbook: flat hierarchy, radical meritocracy, deep ties to the U.S. military, and a culture that treats product building more like art than enterprise software.

Founder Stats

- Technology, AI, Defense

- Started 2015 or earlier

- $1M+/mo

- 50+ team

- USA

About Alex Karp

Alex Karp co-founded Palantir to give America an unfair advantage and still runs it like an anti-playbook startup: flat hierarchy, field deployments, meritocracy, and products built like art for soldiers and frontline workers. Two decades in, he prefers performance over polish, courts retail investors who believe in the mission, and would rather be judged by users than by analysts. Gotham, Foundry, and Apollo follow one rule: stay weird, stay fast, and solve the hard problems others avoid.

Interview

November 21, 2025

You often say Palantir was a “freak show” for almost 20 years. How do you feel now that the company is finally being valued at this scale?

Feels good but still early. For years FDSE, meritocracy, low hierarchy, and betting on America looked crazy. Now the world matches our view, but we still operate like a young freak show. Market cap is nice; pride comes from sticking to our worldview when most thought it would fail.

You describe Palantir as a 20-year-old company with the vibe of a four- or five-year-old startup. What creates that feeling inside the business?

Structure is key: very few layers and lots of direct conversation. Decisions like the meritocracy program can be made in minutes, not months. We keep tribal knowledge from 20 years but move with the freedom of a four- or five-year-old startup. That scale-plus-flatness mix keeps the culture feeling young.

You talk a lot about Palantir as an “anti-playbook” company. What does that mean in day-to-day management?

Anti-playbook means ignoring expert templates and building for people on the ground. We pivoted to the U.S. military or U.S. commercial when it made sense, even if analysts called it insane. If you cannot follow the standard manual, you look at reality and do what helps soldiers and factory teams first.

You come from a family of artists and commercial art. How did that shape the way you build products and run the company?

Art taught me to see what others miss and stick with it. Real art is seeing the era clearly, not doodling. We built PG, Gaia, Foundry, Apollo, and Maven years before acceptance because we believed they captured where the world was going, even if rewards were slow.

In the interview you are very critical of analysts and experts. How do you stop their views from distorting your decisions as a CEO?

The issue is not one mistake; it is that many experts never admit the tenth. They translate reality into their own model, not ground truth. I listen to soldiers, workers, and retail investors. If front-line data conflicts with the expert class, I follow the front line even if it is unpopular.

You say Palantir was built to give America an unfair advantage. How does that belief show up in the way you pick products and customers?

We pick missions that give America an edge in war, counter-terrorism, reshoring, and manufacturing. We see soldiers and workers as people who assumed the world might not work for them yet still fight. That keeps us from building parasitic products; we build tools that make them safer and more effective.

You have become popular with retail investors, especially people on WallStreetBets. Why are you so focused on them?

I grew up outside elite circles. When outsiders put their own money behind us, I take it seriously. Retail investors willing to do the work have earned venture-like returns. If you feel the world is not designed for you, seeing a company that talks differently can be energizing.

You push back hard on victimhood narratives. How does that belief influence how you build teams and culture?

If you embrace victimhood fully, you become a mark. I never expected rescue, even with a messy background. We created meritocratic programs so people tired of discrimination could learn useful skills and compete on output. Inside Palantir the only thing that matters is whether you deliver, not your identity.

You describe yourself as “self-made” more in morals and values than in money. What do you mean by that?

My parents were educated but not wealthy; I went to a poor school and am dyslexic. I could not follow the standard playbook, so I built my own moral system about responsibility and risk. That independence let me stick with Palantir's mission for nearly two decades despite constant criticism.

You often say America is a “maximal freedom culture” that made your career possible. How does that shape your advice to young founders?

America rewards delivery with unusual freedom. I lived abroad, so I see it clearly: you can have eccentric views, write odd letters, run a company like an art project, and if the numbers work you can keep going. My advice: treat that freedom as a competitive advantage and build something others cannot copy.

How is Palantir’s way of creating value different from a traditional SaaS company?

Some software traps clients in dependency. We went the other way with PG and Gotham: start from the mission and build what the client will need tomorrow, not just today. It looked ugly financially for years, but it created deep trust and made the software central to life-and-death work.

You mentioned that FDSE and similar programs were mocked for years. Why did you stay with them?

FDSE put engineers in the field and looked terrible on software margins: lots of travel, messy, low multiples. But it was the only way to push products to their limits and learn the next requirement. If you want next-generation platforms, you sometimes accept ugly short-term optics to learn.

You have a strong connection to soldiers and often talk about awards like the Eisenhower Award. How has that changed your view of leadership?

Outsiders know the world is not designed to protect them. Soldiers and factory workers live with that and still fight. Awards like the Eisenhower Award matter because they signal from that community that our tools helped. Leadership decisions are not abstract; they influence who lives and comes home.

How do you balance being an artist-type founder with the hard financial discipline Palantir shows now?

For 15-plus years many investors thought we were failing financially even as the mission worked. The trick is to keep the artistic, contrarian core but tie it to measurable outcomes. Now that revenue and earnings scale, the numbers buy freedom to stay weird. Performance buys the right to be different.

Internally, how do you make sure people can “be themselves” but still perform at a very high level?

At Palantir you can tell the CEO to move and hold any opinion, but freedom is tied to output. We value people who create for partners in hard environments and give them autonomy. The system works because the value creators in special operations, factories, or data centers get enormous respect and space.

You’ve said dyslexia helped you in a “non-playbook world.” How has that shaped your approach to problem-solving?

Dyslexia taught me I could not win by doing the standard thing slightly better. You either do something different or stay stuck. I am comfortable where there is no manual—war zones, messy politics, strange problems—and I look for the one path that changes the world even if most would fail there.

If you had to give one operating lesson to founders from this phase of Palantir’s journey, what would it be?

Stay brutally close to the real problem for the people who bleed for it, and rebuild infrastructure if needed. Most chase narratives; we tried to ship products that changed behavior for soldiers, workers, and serious investors, even when it offended others. If it works, you end up with something hard to copy.

Table Of Questions

Video Interviews with Alex Karp

Alex Karp, CEO of Palantir: Exclusive Interview Inside PLTR Office

Cite This Interview

Use this interview in your research, article, or academic work

Related Interviews

Mark Shapiro

President and CEO at Toronto Blue Jays

How I'm building a sustainable winning culture in Major League Baseball through people-first leadership and data-driven decision making.

Harry Halpin

CEO and Co-founder at Nym Technologies

How I'm building privacy technology that protects users from surveillance while making it accessible to everyone, not just tech experts.

Morgan DeBaun

Founder at Blavity

How I built a digital media powerhouse focused on Black culture and created a platform that amplifies diverse voices.